To be precise, I am an Indo-Guyanese-American: The mother of all hyphenated identities and an illustration of a historic journey from India to the Caribbean. This heritage is commonly packaged in a number of different terms, all of which are heavily used as referential identifiers: Indo-Guyanese. Indo-Caribbean. Caribbean. West Indian. Indian. It is most aptly described as the Indo-Caribbean experience—an experience that is shared by Indians living throughout the Caribbean diaspora and thus serving as the blueprint for my existence.

This unique cultural disposition is why the Indo-Caribbean are able to culturally identify with public figures ranging from Hasan Minhaj to Nicki Minaj. It is why bursts of Caribbean intonation in Rihanna’s voice blanket me in the comfort of home, while the ballads of A.R. Rahman awaken pained demons within me, crying to connect with a history that was ripped from my hands long before I was born.

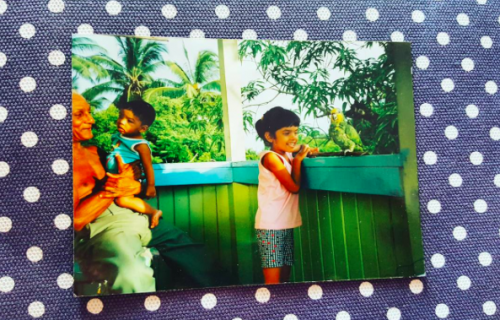

My parents hail from Guyana, a small country on the northern coast of South America. Guyana is one of the original colonies of the British West Indies and, although not located in the Caribbean Sea, the CARICOM Seat of Secretariat is located in Georgetown, Guyana, thus rendering the country a crucial member of the Caribbean family.

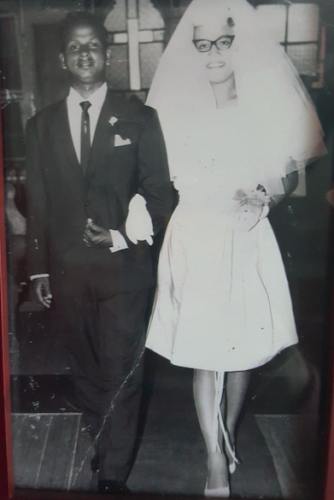

It is home to a number of ethnic and racial identities, including peoples of African, Indian, Chinese, European (primarily Portuguese), and Amerindian (native) descent. Indians comprise the largest ethnic group in Guyana, with Africans following closely as the second largest ethnic group. My family is a multiracial one—I have Indian, African, and Chinese ancestry.

As Queen Mindy Kaling would say, “Fusion, son.”

Despite having this rich, multicultural background, my Indian heritage has played the largest role in both my upbringing and my understanding of myself. It is the heritage that governs the traditions that I’ve grown up with, and that inform my decisions with respect to who I identify as my cultural kin.

In simplest terms, the Indo-Caribbean are Caribbean nationals with East Indian ancestry.

Notably, the transfer of Indians from the subcontinent to the Caribbean/British West Indies occurred pre-partition. As a result, the Indo-Caribbean collectivity generally understands their history as deriving from a singular India regardless of whether their originating territories have been carved into Pakistan, Bangladesh, or some other national designation.

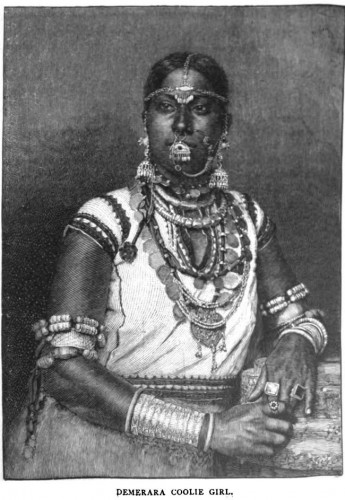

The first Indians to inaugurate the Indo-Caribbean identity were brought from Calcutta to Guyana as indentured laborers subsequent to the official abolition of slavery in 1838, with many belonging to some of the lowest designations of the Indian social system.

While a sizable percentage of the laborers, commonly called coolies, were recruited from the (modern) northern Madhya Pradesh and Bihar regions, many Indians also came from the Tamil and Telegu regions of South India. Our history books equip us with the term “recruitment” for characterizing the colonial transfer of Indians to the British West Indies, however, it is noteworthy to highlight that many Indians were “recruited” by means such as kidnapping or being placed into forced detention. These were practices that resulted from the realization of the desperate need to replace lost slave labor in an expedient manner subsequent to the abolition of slavery.

Women were the most vulnerable to this form of “recruitment” and many were commonly used by their European managers for sex while working on plantations. Some laborers were able to achieve repatriation. Many, however, never returned home again.

Upon their arrival in Guyana, the Indians were met with great hostility from the existing working class of newly freed slaves in Guyana.

“Do not speak to the Indians,” said the British to the Africans. “They are vile and carry diseases.”

Accordingly, the first Indo-Guyanese dwelled in isolated communities where they were identically indoctrinated to despise their new countrymen.

“Do not speak to the Africans,” said the British to the Indians. “They are vile and carry diseases.”

It was a strategy to prevent the union of the groups. Together they would be strong enough to rebel against their oppressors. This racial tension between the Indo-Guyanese and the Afro-Guyanese has endured throughout the development of Guyanese history—well after independence from Britain and right up to the most recent Guyanese presidential elections in 2015.

[Read More: Gaiutra Bahadur Shares Journey of Coolie Women From India to Guyana in New Book]

Sometimes, I refer to myself as simply “Indian” even though many South Asians would not regard me as such. It is often just easier to provide an answer that people can easily understand rather than undertake the laborious process of explaining the geographic quandary of being brown but not directly from South Asia.

Language plays a large role in this distinction.

The Indo-Caribbean do not generally speak the native languages that our ancestors brought with them from the subcontinent. The Hindi and Tamil that history books explain were largely spoken by the indentured laborers have died along with our great-grandparents. Once in a while my paternal grandmother sings Islamic devotional couplets in Hindi and explains what she understands them to mean based on her grandparents’ translations of them decades ago.

Outside of religious devotional songs and prayers, however, the Indo-Caribbean speak the same English creole as their national counterparts of different ethnicities—an anamorphic brand of English that can only be formed by a people ripped from their lands and forced to place a strange language on their reluctant tongues. A patois infused with words gleaned from both African and Indian dialects. This linguistic separation is the key factor contributing to our isolation as a separate cultural tradition.

My parents never wanted me to imitate this accent because, for many, it is regarded as a thing of shame. To be hidden away like a botched tattoo or a drunken mistake. It is an illustration of how the poorest members of Indian society spoke when English was first forced upon them.

“Speak properly!” my parents said, when I playfully accented my words. “You are an American.”

For the record, I learned to speak this way flawlessly nonetheless, as a result of my parents’ own relentless use of this creole at home.

“You are not Guyanese-American. You are just American. You were born here.”

On the multi-cultural day at school, they didn’t understand why I had to create a poster about Guyana.

“You are American. Make a board about America, nah?”

This was a phenomenon that my first generation counterparts in other cultures did not seem to endure as they proudly donned their Indian-American, Chinese-American, or Italian-American hyphenations.

Though my parents surely meant well, preventing me from embracing my culture for the sake of proliferating my American identity severely deprived me of being able to relate to my existence the way I deserved to know it.

While I can understand why immigrant parents would want their children to benefit from the privilege of American identity stripped from immigrant implications (and all of the colonial implications that accompany those desires), the realities of American life aren’t so easily accepting just because one can speak “properly.”

It was because of this initial deprivation that I felt devastatingly lost when I was just five years old. A Caucasian classmate once told me that her parents didn’t want us to be friends because my skin was darker than her own. It didn’t make sense and I still remember it so vividly: the way she put her arm up next to mine as though presenting probative evidence in court.

“You see? Look how different we are!”

I spoke “properly” and did all of the things my parents thought I had to do in order to be American. They told me that this “American” heritage belonged to me and, yet, at the age of five I had been so harshly excluded from what I thought was my own village. It didn’t matter how I spoke or acted. I looked different and that was all that mattered. For the first time I started looking for people who looked like me.

[Read Related: Queens Girls: Indo-Caribbean Life in ’90s New York]

I remember being desperately confused and looking frantically around the classroom. My eyes met with another classmate—an Indo-Caribbean girl named Jasmine, who had witnessed the whole debacle. We didn’t know each other, yet when our small eyes connected, she gave me an encouraging smile. Her hanging gold earrings, shaped like a bunch of grapes, were glistening under the fluorescent classroom lights. She moved to Connecticut before the end of the school year, but I still remember her face so well. The first person to console me after my first bout of colonial trauma. It was as though we were kindred spirits. As though in that moment our hearts were screaming:

“Where have you been?! I nearly drowned without you.”

It is why, one day, while working at a Bronx courthouse mediating claims, a confused Guyanese woman in the small claims office bypassed the dozens of staff members at her disposal and asked me to help her navigate the application process. “Where have you been?! I nearly drowned without you.” Yet again, rings true.

Despite my parents’ efforts to remove the hyphenations of my identity, fueled by genuine concerns gleaned from their immigrant experience, they ironically never took issue with my connection to Indian culture.

The Bollywood film industry is and always has been one of the primary means through which the Indo-Caribbean have been able to remain connected to their heritage. This prevalence, however, has resulted in the prevailing Indo-Caribbean understanding of their Indian roots to be deeply colored by north Indian traditions—as they are exemplified in these films—despite the sizable population that is actually of South Indian origin.

Nonetheless, this tradition of Bollywood devotion was sustained in my home in Queens, NY, where my family and I watched every ’90s Bollywood film worth watching and I developed adoration for the King Khans just as much as a direct South Asian descendant.

I venerated the Indian traditions at my disposal just as much as I did the traditions that West Indians have carved out over time by way of Caribbean music and unique fusion cuisines. While my mom prepared meals of curried shrimp and roti, she would dance to Byron Lee and The Draggonaires. While my dad idolized Bob Marley as a musical genius, he also made me aware of the significance of Amitabh Bachchan vis-à-vis arduous debates with his brothers about relevant actors in that industry.

For me, these were all equally important histories and they existed concurrently with a surprising serene ease. It is a harmony that comes to me as naturally as hunger or sleep.

Notwithstanding, these commitments to cultural retention, the Indo-Caribbean are generally rejected from the desi family by South Asian communities that carry more puritan views of cultural identity.

- We don’t speak the language.

- We were removed from the subcontinent.

- We descend from the lowest rungs of the then existing hierarchy of social class.

- We delight in soca music while preparing our curries.

What a strange group we are.

I associate my parents’ past desire to strike Guyana from how I self-identify (yet toward Indian traditions) with the same ideals that legitimize the rejection of the Indo-Caribbean in South Asian communities: shame.

It is a shame that we don’t understand Tamil or know whether we’re from UP or MP. It is a shame that we’ve developed this hybrid culture, gleaned from traditions all over the world and thus losing the clarity that comes with having a single heritage.

Trauma begins when the first Indian laborers were forced to forget their native tongues, and re-emerges when the Indo-Caribbean were ostracized for not retaining those very dialects.

Trauma begins when your colonizers use your ancestral grandmother as a sex slave, and re-emerges generations later as the Indo-Caribbean standard of feminine beauty becomes characterized by how Indian a woman doesn’t look.

“She’s so pretty—she doesn’t even look like a coolie girl.”

For why would we venerate a female form that has already been pillaged by our oppressors?

Trauma begins with the brutal transfer of Indians to the West Indies and re-emerges when their progeny seek to strike their relevance from their identities.

I do not find shame in my double diaspora. To do so—to reject being Indian or of Indo-Caribbean heritage—would be to renounce those who came before me and endured largely untold pain. Sporting sarees, devouring South Asian cuisine, and singing Hindi film songs passionately from our stomachs: we call America home but still extend our fingertips to a motherland that moves further and further away with blood, tears, and rejections in its trail. We are a people born from trauma and tragedy. A flower that dares to bloom against a backdrop of grime and pain.

Elizabeth Jaikaran is a freelance writer based in New York. She graduated from The City College of New York with her B.A. in 2012, and from New York University School of Law in 2016. She is interested in theories of gender politics and enjoys exploring the intersection of international law and social consciousness. When she’s not writing, she enjoys celebrating all of life’s small joys with her friends and binge watching juicy serial dramas with her husband. Her first book, “Trauma” will be published by Shanti Arts in 2017.

Elizabeth Jaikaran is a freelance writer based in New York. She graduated from The City College of New York with her B.A. in 2012, and from New York University School of Law in 2016. She is interested in theories of gender politics and enjoys exploring the intersection of international law and social consciousness. When she’s not writing, she enjoys celebrating all of life’s small joys with her friends and binge watching juicy serial dramas with her husband. Her first book, “Trauma” will be published by Shanti Arts in 2017.